My guess is that the piece was written by a local landowner, M.D. Williams, the brother of Isaac Williams who was a Tractarian (Oxford Movement) theologian and poet, and had been Cardinal Newman's curate before Newman became a Catholic. Williams lived in Plas Cwmcynfelin, a house about a mile north of Aberystwyth. He built a church in Llangorwen, the village overlooked by Plas Cwmcynfelin, which was built very definitely with ritualism in mind, in accordance with principles put forward by the Tractarians. Alternatively, it might have been written by the vicar of Llangorwen. (Plas Cwmcynfelin is now a care home.)

It was not uncommon to find high churchmen in Wales who were sympathetic to Welsh nationalism as it existed at the time - they were keen to see the Welsh church separated from Canterbury - and their interest in the medieval meant that they were attracted by the old Welsh literature.

One wonders how the anti-nonconformist tone went down. On the other hand, such generous praise from a highly educated writer must have done Parry good in a lot of circles. I wonder how he felt about being lavishly praised while his denomination was castigated along with others like it.

Dr Parry deserves the sincerest gratitude of all music-loving Welshmen for stepping out of the ordinary paths, and producing a specimen of the art of music which no Welshman before him has ventured to attempt. Dr Parry has composed a Welsh Opera which will, undoubtedly, enrich the music of a musical nation, and serve at the same time to enkindle and encourage the highest duties and feelings of the people. The opera, entitled Blodwen , is based upon an incident in the history of the Welsh in the fourteenth century – a period full of thrilling interest, being the time when the Welsh, under Owen Glendwr, made the last attempt to retain their independence(1). The Welsh words were written by Mynyddog, and the English, a free translation, by Professor Rowlands, of Brecon College.

Our readers are already aware of the “argument,” and it remains only to state, briefly, that the first performance passed off with almost all the success which it is possible to attain in a provincial town of the size of our own. In the afternoon the Temperance Hall was well filled, the elite of town and county society, within several miles, being present or represented. This is a most flattering compliment paid to Dr Parry, and is second only to the approbation of the Princess of Wales, who has been pleased to accept the dedication of the opera, and will be correspondingly appreciated by him. The evening concert was literally crowded by a highly appreciative audience. The stage was somewhat adorned with drapery, bearing various mottoes and appropriate devices. The principal actors – although, as Dr Parry explained at the commencement, there was no attempt at acting – were attired in costumes characteristic of the period when the scenes are laid. The singing of the choir was capital, especially in the Hunting Choruses, which are deserving of a place with the best of their class; the effect of “the echo awakening again and again” was charming. The warlike pieces were forcibly expressed, and the bard was well represented by Mr R. C. Jenkins, who continues to advance in power and refinement. A pretty little scene is that where “the huntsmen having sped through the valley,” Sir Howell Ddu seeks the shade of the holly, and sings a song in praise of Blodwen, who, fortunately for him, happens to be on the other side of the bush, and hearing his love-sick melody, finds a means of delicately helping him out of his difficulty; otherwise there is no knowing when he could have uttered words to express his love. In the first act Ellen of Maelor Castle is married to Arthur of Berwyn Castle, who is afterwards slain in battle, but not before doing sad havoc amongst the enemy. Lady Maelor appears frequently, and renders her songs with expression and pathos. Mr Lucas Williams, who undertakes three parts, is possessed of considerable ability, and the minor characters are sustained with good effect. The concerts were conducted by Dr. Parry, and his two youthful sons accompanied on the pianoforte and harmonium. At the present day, when some of our nation – a noisy few – are inculcating the dangerous principles of comfortable selfish living, and the dreaming away of life, without giving a thought to commonwealth, – the manly and patriotic tone of the words and music will have their due effect.

Soprano Primo–“Blodwen” (Daughter of Rhys Gwyn, supposed to have fallen in battle) . . . . . Miss Hattie Davies, U.C.W.

Soprano Secondo–“Ellen” (Daughter of Lady Maelor) . . . . . . . Miss Gayney Griffiths, U.C.W.

Contralto–“Lady Maelor” (of Maelor Castle) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Miss Annie Williams, U.C.W.

Tenore Primo–“Sir Howell” (The Knight of Snowdon Castle) . . . . . . . Mr Thomas Evans, U.C.W.

Tenori Secondo–“Lady Maelor's Messenger,” and a Soldier from the Army of Henry IV. Messrs D. Howell and W. Davies, U.C.W.

Baritones–“Arthur” (A Welsh Warrior), “The Monk” “Rhys Gwyn (Father of Blodwen) . . . . . Mr J. Lucas Williams, from the Crystal Palace Concerts, London

Basso Primo–“The Bard” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr R. C. Jenkins, late of U.C.W.

Chorus–Servants, Castle Keepers, Huntsmen Soldiers, Prisoners and the People.

Accompanists, Piano– Master Joseph Haydn Parry; Harmonium– Master David Parry.

“A prophet is not without honour save in his own country.” There are exceptions to every rule, and there is scarcely a proverb which has not proved to be inapplicable to certain cases. In the ordinary course of everyday life, however, we are constantly being brought face to face with the fact that, in respect to rules and proverbs alike, there is a very strong undercurrent of truth which cannot be gainsaid. In listening to a performance of Dr. Joseph Parry's “Saul of Tarsus” tonight in this busy Metropolis of the North (3), the writer of this notice, who is not unfamiliar with the state of matters musical in the Principality, could come to no other conclusion than that the familiar quotation that stands at the head of these remarks is particularly applicable to the case of Dr. Joseph Parry. It would be wrong, of course, to say that Dr. Parry has not his admirers in Wales, or that he is not esteemed – and most highly esteemed – by the majority of his countrymen, but it would be far from the truth to say that he is generally appreciated at his true value by those amongst whom he labours. It is not too much to say that the undoubted gifts and attainments which Dr. Parry possesses entitle him to rank amongst the greatest living composers, not only of this, but of any country. It must not be surmised that these remarks are penned by a mere novice carried away by the enthusiasm of the moment – they are written by one who has attended nearly all the great festivals held in this country during the past twenty years (including those of Birmingham and Leeds, where most of the important musical works, from “Elijah” downwards, were first introduced to the world), and who does not hesitate to say that “Saul of Tarsus” is worthy of a high position amongst festival works of the present day. That Dr. Parry has accomplished so much in the face of such difficulties as he has been beset with and hampered by such restrictions as have been placed upon him is truly marvellous. It is impossible to say what he might have accomplished if he had been favoured with the advantages, of hearing his own works adequately performed, as have been accorded to the foremost English composers – indeed, our festival committees in search of novelties could hardly do better, even now, than encourage the production of another such work as “Saul of Tarsus” from the same pen.

Dr. Parry arrived in Newcastle on Saturday, and previous to the performance to-night had the advantage of rehearsing several times with principals, choir and orchestra. He came to Newcastle absolutely unknown save to a few musical enthusiasts (4) – for a reputation made in Wales does not reach these remote regions – but he will leave the North with a reputation that anyone might envy. In the course of three days he has gained hosts of admirers amongst a people who, having frequent opportunities of hearing the greatest works and the greatest artistes of the day, are ever ready to appreciate true merit when it comes before them. It may be safely said that a ready and hearty welcome will always await Dr. Parry should he at any future time choose to visit this locality.

To give a detailed description of “Saul of Tarsus” in the columns of the “Western Mail” would somewhat resemble the process of “carrying coals to Newcastle”. The work was heard at Cardiff at the first festival of 1892, and was fully discussed at the time; but there is no denying the fact that it did not receive full justice on the occasion, and that its manifest beauties were not so apparent, and were consequently, not so highly appreciated as they might have been. It is surprising, indeed, that the oratorio–unquestionably the finest sacred musical work ever written by a Welshman–has not been since performed in Cardiff, and, on the principle that it is “never too late to mend,” it may be hoped that an opportunity of re-hearing it may not be far distant. The work is replete with beautiful and effective numbers, and could only have been written by a man endowed with the highest qualities of the true musician. Is proof of this assertion wanting? Why, every page of the score stands out in confirmation of it! Turn to the beautiful strains of the second scene, illustrative of “Morning,” and compare the gentle and melodious phrases of the Jewish women with the uncouth but effective music of the Roman Guards! Examine the music of the prison scene with its beautiful melody for “Silas” and its grand and impressive finale descriptive of the earthquake! Listen to the Christians' morning hymn in the third scene, a delicious gem of part music in which the “Sunrise” theme is so effectively intertwined with the voices! Turn again to the fine chorus of Levites and people in the Temple Scene and to the clever fugue which closes this scene! To the charming trio which opens the Prison Scene, and, by way of contrast, to the “festive music” in the same scene! And to the stupendous fugue in the final scene of all! These are features striking enough to prove our assertion over and over again. It is only after carefully analysing and hearing such a work as this that its remarkable cleverness and many beautiful effects can be truly appreciated. The ordinary listener does not discover the ingenuity with which the numerous leading motives (representative themes) are introduced, but the cultured musician will discover far more in the work than he expects to find there. Without going further into detail, it may be truly said that the work is one which is not only a monument to the talent and industry of its composer, but which every Welshman may point to with confidence as the worthy production of a man whom they are proud to honour as the greatest of their native composers.

The Welsh Representative Choir, comprising 100 persons of both sexes, have today visited Cambridge, on the occasion of the admission of Professor Parry, of the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth to the degree of Doctor of Music (2). The choir of Professor Parry left Wales yesterday, and proceeded to London, journeying thence to Cambridge today, and proceeding at once to the magnificent chapel of King's College (3), which, with the ante-chapel, is supposed to be the largest building in Europe unsupported by pillars. The guests had hardly time to admire the grand architecture of this spacious building and the magnificently painted window ere they had to rehearse the sacred exercise which was afterwards given with great success by the choir. “Jerusalem or Judgment and Mercy,” is a sacred exercise composed by Professor Parry for his degree of Musical Doctor. The choir was composed chiefly of colliers and colliers' wives and children from Aberdare, Neath, and Mountain Ash, with some trades people, and about 20 musical students of the University at Aberystwyth. They were divided into two choruses; there were about a dozen in each of the sopranos, about ten in each altos, eleven first tenors, ten second tenors, and twelve in each of the basses. The choir has already given the exercise at Aberdare and Pontypridd, and they repeat it next week at Bristol, Newport, Cardiff, and Swansea. Today the attendance was not large, as, except in a small circle, it was not known that the exercise would be sung by such a choir. Amongst those present, however, we noticed Professor Macfarren (4), Mr. Sedley Taylor (5), Mr. G. F. Codd, Mr. Oscar Browning (6), and other musical critics. Mr. Mann, the talented organist of King's College, presided at the organ, and Professor Parry himself conducted. Mr. Mann played the overture, after which the grand double chorus sang “O Jerusalem,” the quartette being given by Miss Adelaide Morgan, Miss Eleanor Rees, Mr. W. Davis, and Mr. R. C. Jenkins. The quartette was well rendered. The third movement consisted of a very sweet chorale, “My Jesus, as Thou wilt, when Death itself draws Nigh,” and the way this was sung was exceedingly fine. After this came a recitative, “Behold the day of the Lord cometh,” and air, “But the Lord will remember His children,” which were given by Mr Lucas Williams, who possesses a magnificent bass voice, and who used it well in spite of a little nervousness. Then came another very nice chorale, “Inspirer and hearer of prayer,” after which, with the double chorus, “We magnify and glorify Thy name,” the exercise concluded. At the end of the performance, Professor Macfarren congratulated Professor Parry on his work, and, addressing the choir, said their vocal efforts had been very successful in spite of the echo of the large building, which seemed sometimes jealous of the beautiful voices. The organ had also done its share of the work well. Professor Macfarren added that he should like to hear it with a full band. This had been on the whole a most satisfactory performance so far as the acoustic properties of the chapel would allow. It was a credit to Cambridge, and they were a credit to the Principality from which they came. The interval between the conclusion of the musical performance and the ceremony at the Senate House would have been spent by the choristers visiting some of the sights of the university, but a drenching shower of rain came down, and not only prevented them from peregrinating the colleges, but also postponed the holding of the congregation for some time, as the Vice-Chancellor was unable to get from Clare Lodge to the Senate House. Professor Parry's musical friends nearly filled all the seats on one side of the Senate House. They appeared to be very much amused with the proceedings, there being another Master of Arts to be admitted as well. Fortunately for them, the undergraduates' galleries were all but deserted, and neither the professor nor his Welsh friends had to run the gauntlet of undergraduate chaff, all the members of the university in statu pupillari having gone down, or nearly so. The floor of the Senate House presented its usual animated aspect on Congregation day, which was rather intensified by what may be regarded as something very like a hitch. The conferment of the Doctor's Degree on Professor Parry was evidently not contemplated, as no supplicat (7) was prepared, and on the arrival of Dr Atkinson, the Vice-Chancellor, preceded by the two Esquire Beadles bearing the mace, at about half an hour after the regulation time, it was found necessary to hastily convene a meeting of the council. Ultimately the Senior Proctor submitted the grace or proposition to the Senate that Joseph Parry should be admitted to the degree of Mus. D., and declared it placet , that is, carried. After an M.D. had been admitted, Professor Parry, who wore a scarlet gown with violet lining, was directed by the Rev. F. Watson, M.A., the father of St. Johns, to take his position in the centre of the floor of the Senate House, facing the dais, on which sat the Vice-Chancellor wearing a doctor's hood. Here Professor Macfarren was brought to him by Mr. G. F. Cobb, M.A., the Bursar of Trinity, and conducted Professor Parry to within half a score yards of the Vice-Chancellor, when the Professor of Latin (8) introduced the doctor designate to the Vice-Chancellor in the following terms:– “ Dignissime domine, procancellario et tota academia, presento vobi s hunc verum [sic ] , quam scio, tam moribus quam doctrina, est idoneum ad titulum doctoris designati assequendum in musica; atque tibi, fide mea presto, totique academiæ.(9)” This done, the professor of music retired, and the new doctor designate advanced up the first step of the dais, and knelt at the feet of the Vice-Chancellor, who, taking his hands between his own, admitted him in the following words: “ Auctoritate mihi commissa, admitto te ad titulum doctoris in musica designat i , in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. (10) ” Professor Parry rose from his knees a fully fledged doctor of music, and the ceremony was at an end in so far as Dr. Parry was concerned. The Welsh representative choir did not disperse but remained with evident interest to the end, the congregation watching the ceremony of the admission of 26 masters of arts and three bachelors of arts. Dr. Parry was entertained by some of the leading musical members of the university, and the rest of the party dispersed about Cambridge, to reassemble at the Great Northern Railway Station shortly after four o'clock, whence they left the university by the 4.30 train for London after a visit whose agreeable character was only curtailed by the wetness of the weather. Of the merits of Dr. Parry's music it is unnecessary to speak, as your readers will have an opportunity of judging for themselves next week on its production at Cardiff, &c. The singing of the choir was characterised by much vigour and freshness, and the chorales were characterised by much sweetness. One could only have wished that the visit had been publicly known, that the spacious chapel might have been filled, and so the echo have been obviated.

(1) 13 June 1878

(2) The universities of Oxford and Cambridge have awarded the degrees of Bachelor of Music and Doctor of Music since the fifteenth century but until the twentieth century these were external degrees: the universities did not offer teaching in music and candidates for the degrees did not have to spend time residing in the university. Apart from a few formalities, candidates had simply to take examinations and submit a work that they had composed. (In the case of the doctorate, it was also required that the work be performed.) The degree was essentially a professional qualification. It is a misunderstanding of this that has led to the mistaken assertion, commonly found on the World Wide Web, that Parry studied at Cambridge.

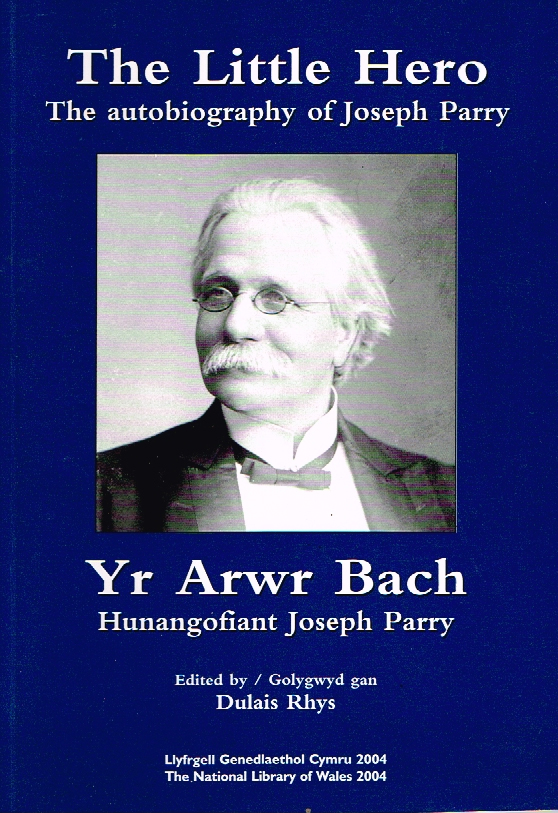

(3) This article shows that To Philadelphia and Back: the life and music of Joseph Parry (Rhys and Bott, 2010) is mistaken in giving St John's College Chapel as the venue of Parry's doctoral performance, based on the composer's mistaken recollection in his autobiography.

(4) Sir George Alexander Macfarren (1813-1887). Musicologist and composer, he held the Chair of Music at Cambridge from 1875 and was Principal of the Royal Academy of Music from 1876. He was almost blind for much of his life. He composed nine symphonies, and numerous operas, operettas and choral works, none of which survived into the twentieth century repertoire. Parry dedicated his oratorio Emmanuel to him.

(5) Sedley Taylor (1835-1920). Cambridge academic who, as a competent physicist and musician, did pioneering work on the physics of music. He was also distinguished as an economist and was a noted philanthropist.

(6) Oscar Browning (1837-1923). Distinguished historian, literary scholar and wit.

(7) A formal document requesting that candidates be admitted to their degrees. It had to be prepared by the Council of the Senate and approved by the Senate itself before the Vice-Chancellor could admit them.

(8) This is probably an error. The candidate would normally be presented by the Praelector of his College, St John's in Parry's case. It is possible but highly improbable that the Praelector of St John's at the time happened to be the Professor of Latin.

(9) “Most worthy masters, Vice-Chancellor and the whole university, I present to you this man, whom I know is suitable, as much by character as by learning, to be designated with the title of doctor of music; and to you and to the whole university I thus pledge my faith.” The Latin as quoted contains several minor errors, notably verum (truth) for virum (man).

(10) “By the authority granted to me, I admit you to the title of doctor of music, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

The Birth of Myfanwy

Rhidian Griffiths (translated by Frank Bott)

(An invited article published in Yr Aradr, the journal of Cymdeithas Dafydd ap Gwilym , the Oxford University Welsh Society . Translated by Frank Bott and included on this web site by kind permission of the author.)

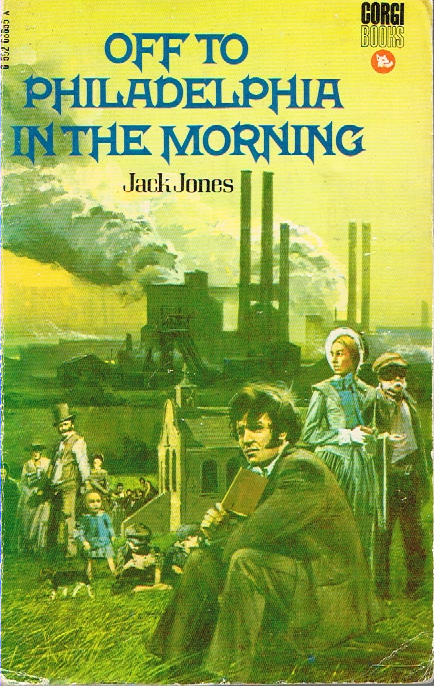

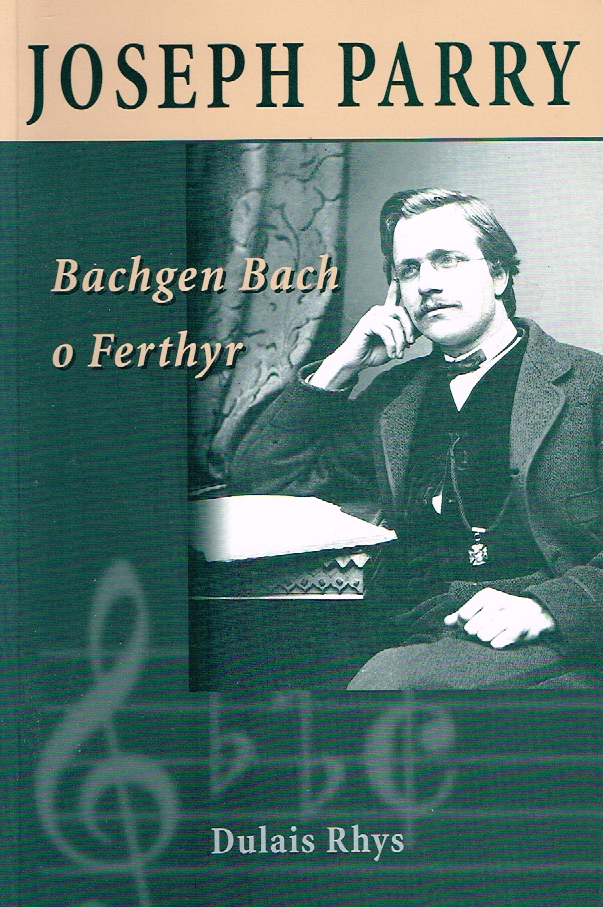

She is one of the nation's most famous women, dear to many, ridiculous to some. Wherever there are male voice choirs, within Wales or abroad, Joseph Parry's arch-Victorian, sentimental, simple part-song about her will be sung. To many, especially the Welsh in exile, it epitomizes traditional Welshness and personifies their hiraeth (1) for the old country. It was created by four men: Thomas Gwallter Price, ‘Cuhelyn' (1829-69), author of the English poem ‘Arabella'; Richard Davies, ‘Mynyddog' (1833-77), who wrote the Welsh poem under the title ‘Myfanwy'; Joseph Parry (1841-1903), the colourful and talented musician who wrote the music for it; and Isaac Jones (1835-99), the publisher from Treherbert in the Rhondda, who first presented it to the world in 1875 (2).

It can be said of Cuhelyn as of ‘man that is born of woman' that his days were few and full of trouble. During his short life he was in trouble time and time again, so much so that it was suggested that he should have taken ‘Cuhelynt' as his bardic name rather than ‘Cuhelyn' (3). He had a tumultuous career as a journalist and newspaper editor in North America, and was fined and sent to prison for libel. But he was also interested in poetry and was a friend of John Jones, ‘Talhaiarn'. He it was who brought Llew Llwyfo to the United States in 1856 to entertain the Welsh there, and in 1857 he started a weekly newspaper called Y Bardd [‘The Bard'], and arranged for writers from Wales to contribute to it. His poems appeared in his own newspapers and in the pages of other Welsh newspapers published in North America, and their style is typical of their period. Here, for example, is his englyn (4) to the sun, which appeared in Y Drych a'r Gwyliedydd [‘The Mirror and Sentinel'] on 25 April 1857:

Dëon haf wrth dy neifion, – drws eurawg

I drysorau'r Cristion;

Gwiw lywydd pob goleuon, twf a gwres,

Yw yr Haul eres, O! arial wron.

|

Lord of summer from thy heaven, – gilded door

To the Christian's treasures;

Fit leader of all light, growth and warmth

Is the wondrous Sun, O! valiant hero.

|

The same high-flown poetic style is to be found in his English poem, ‘Arabella':

Why shoots wrath's lightening, Arabella,

From those jet eyes? What clouds thy brow?

Those cheeks that once with love blushed on me,

Why are they pale and bloodless now?

Why bite those lips that bare [ sic ] my kisses?

Where lurks the smile that won my heart?

Why wilt be mute, Oh, Arabella,

Speak, love, once more before we part.

What have I done, Oh, cruel fair one,

To merit e'en a frown from thee?

Am I too fond, or art thou fickle,

Or play'st thou but to humble me?

Thou art my own by word and honour,

And wilt thou not thy word fulfil?

Thou needs't not frown, Oh, Arabella,

I would not have thee 'gainst thy will.

Full be thy heart with joy forever,

May time ne'er cipher on thy brow;

Through life may beauty's rose and lily

Dance on thy healthy cheeks as now;

Forget thy broken vows, and never

Allow thy wakeful conscience tell

That thou did'st e'er mislead or wrong me;

Oh, Arabella, fare thee well.

I don't know where this was published, if indeed it was published at all before it appeared in Joseph Parry's setting. It must have been written before 1869, the year of Cuhelyn's death; and since Parry spent the period from 1854 to 1874 in the United States (apart from a period of study in London) in the state of Pennsylvania, where Cuhelyn himself also lived, it's highly likely that they knew each other. Parry could have got the words from the poet himself or have taken them from an American publication. Is ‘Arabella' therefore the original poem rather than ‘Myfanwy'? That is what is stated in a review of the first edition of the song, and the circumstantial evidence supports this view, even though the copy places the Welsh words above the English ones (5).

I don't know of evidence relating to the time that Parry made his setting, although the tradition noted by Emrys Cleaver indicates that it was after he came to the Chair of Music in Aberystwyth in 1874 (6). With regard to the ‘independent' existence of Cuhelyn's poem, it's worth noting also that another musical setting of it appeared in 1893. This setting, for male voices, was made by T.J. Davies, a musician from the Swansea area who had moved to North America; it was published by D.O. Evans in Youngstown, Ohio. In this setting ‘Arabella' turns into ‘Leonora', but it is the same poem:

Why burns deep anger, Leonora,

In those blue eyes? What clouds thy brow?

Those cheeks that once with love blushed on me,

Why are they pale and mirthless now?

Why cool those lips that bear my kisses?

Where lurks the smile that won my heart?

Why wilt be mute, Oh, Leonora,

Speak, love, once more before we part.

There are no Welsh words at all to be seen in this setting, neither ‘Myfanwy' nor anyone else.

Mynyddog, author of the Welsh words that appeared in Parry's setting, was a poet and popular entertainer, and a leader of eisteddfodau and concerts second to none. He published three volumes of poetry during his lifetime, Caneuon Mynyddog [‘Songs of Mynyddog'] (1866), Yr Ail Gynyg [‘Second Volume'] (1870) and Y Trydydd Cynyg [‘Third Volume'] (1877), but ‘Myfanwy' appears in none of these. However, we know for certain that Mynyddog wrote many song lyrics, including translations and adaptations of English and American songs. We also know that the publisher Isaac Jones commissioned Mynyddog to write lyrics: in June 1875 he was writing to Gwilym Gwent in Wilkesbarre, PA, asking him to compose music for Mynyddog's lyrics ‘Y Teiliwr a'r Crydd' [‘The Tailor and the Cobbler'], written ‘at my request' (7). It is thus very likely that it was at the publisher's request that Mynyddog wrote his poem to accompany Parry's setting. These words were to make their mark, probably because they are so much better than Cuhelyn's text:

Paham mae dicter, O Myfanwy,

Yn llenwi'th lygaid duon di?

A'th ruddiau tirion, O Myfanwy,

Heb wrido wrth fy ngweled i?

Pa le mae'r wên oedd ar dy wefus

Fu'n cynnau 'nghariad ffyddlon ffôl?

Pa le mae sain dy eiriau melys,

Fu'n denu'n nghalon ar dy ôl? |

Why is anger, O Myfanwy,

Filling your dark eyes?

And your gentle cheeks, O Myfanwy,

Why aren't they blushing when you see me? Where is the smile on your lips

That kindled my love so fond and true?

Where is the sound of your sweet words,

That drew my heart to follow you? |

Pa beth a wneuthum, O Myfanwy

I haeddu gwg dy ddwyrudd hardd?

Ai chwarae oeddit, O Myfanwy

thanau euraidd serch dy fardd?

Wyt eiddo im drwy gywir amod

Ai gormod cadw'th air i mi?

Ni cheisiaf fyth mo'th law, Myfanwy,

Heb gael dy galon gyda hi. |

What have I done, O Myfanwy,

To earn the frown of your lovely cheeks?

Were you playing, O Myfanwy,

With the golden strings of your poet's love?

You are mine in truth,

Is it too much to keep your word to me?

I shall never seek your hand, Myfanwy,

Without getting your heart with it. |

Myfanwy boed yr holl o'th fywyd

Dan heulwen ddisglair canol dydd.

A boed i rosyn gwridog iechyd

I ddawnsio ganmlwydd ar dy rudd.

Anghofia'r oll o'th addewidion

A wneist i rywun, 'ngeneth ddel,

A dyro'th law, Myfanwy dirion

I ddim ond dweud y gair "Ffarwél". |

Myfanwy, may you spend your lifetime

Beneath the bright midday sun,

And may the roses of good health

Dance on your cheeks for a hundred years.

Forget all the promises

You made to someone, my pretty girl,,

Give me your hand, my sweet Myfanwy,

Just to say the word "Farewell". |

In 1882, five years after Mynyddog died, Isaac Jones published a volume of lyrics written by the poet for songs that appeared from the Jones press. In Pedwerydd Lyfr Mynyddog (8) twenty-four Welsh lyrics appear along with the corresponding English words; among them are ‘Myfanwy' and ‘Arabella'. It is not stated that one is a translation of the other, but the fact that Isaac Jones published the collection suggests the Mynyddog lyrics were his property , and had perhaps all been written at his request.

Joseph Parry's setting appeared as one of a series of six pieces that Isaac Jones published in 1875. The title given to the series, for which the publisher paid the composer £12 (9), was Telyn Cymry [‘The Harp of the Welsh' but again the Welsh is grammatically incorrect – it should read ‘Telyn y Cymry']. The six pieces in the series were in six different musical forms: a glee, ‘Y cychod ar yr afon ' [‘The boats on the water']; a chorus for mixed voices, ‘Maesgarmon', in fact, an arrangement of ‘Men of Harlech'; a duet, ‘O mor hardd yw breuddwyd awen' [‘O how beautiful is the dream of inspiration']; an anthem ‘Pebyll yr Arglwydd' [‘The Pavilions of the Lord']; and a solo song ‘Ysgydwad y llaw' [‘The Handshake' (10)]. ‘Myfanwy', a part song for male voices was the sixth. It is significant that it was Mynyddog who wrote the Welsh words for four of these pieces (the exceptions were ‘Y cychod ar yr afon' and ‘Pebyll yr Arglwydd').

The pieces in this series were the only works of Joseph Parry that were published by Isaac Jones. Jones himself had been raised in the Swansea Valley and set up a printing business in Treherbert in 1872, and was printing and publishing there until his death in 1899. He published booklets of poetry by local bards and more substantial works such as a volume of sermons by Islwyn (11). His main contribution, however, was his work in publishing music and the music periodical , Cronicl y Cerddor [‘The Musician's Chronicle'], which appeared from July 1880 to June 1883. He began publishing music around 1874 and the series Telyn Cymry was among the first publications that came from his press.

‘Myfanwy' was first performed (in Welsh so it appears) in the opening concert of the Aberystwyth and University Musical Society on 21 May 1875 (12), in a programme typically full of Parry's own works(13). It was reviewed in Y Gerddorfa for June 1875 (vol. 3, p.44):

This little song is distinguished by its simplicity . . . The piece owes its effectiveness to the richness of the voices and correct use of dynamics, but if these are properly observed the song will certainly be very effective . . .

Ten tears later, in October 1885, a review of the American edition of the song appeared in Cerddor y Cymry, where it was said that ‘Myfanwy' was ‘well-known in this country' (vol.3, p. 51).

The song was certainly sung many times before Joseph Parry died in 1903. But it was perhaps the Morriston Orpheus Choir under the baton of Ivor E. Sims that brought it to the pinnacle of its popularity in the twentieth century, although by then it was no longer published by Isaac Jones' company. In 1930, the musical titles of his press were sold to D.J. Snell of Swansea, and he it was who republished ‘Myfanwy' in 1931. Snell and Sons continues to sell copies, so great is its popularity, and it appears there is now nothing to hinder the inexorable onward march of the song born in Treherbert in 1875. For better or worse, ‘Myfanwy' is part of the inheritance of the Welsh.

The word hiraeth means ‘nostalgic longing' or ‘yearning'. It is notoriously difficult to find a precise English equivalent. Tr.

Information about Cuhelyn and Mynyddog can be found in Y Bywgraffiadur Cymreig hyd 1940 (London, 1953). For Isaac Jones, see Rhidian Griffiths, ‘Isaac Jones: music printer and publisher'. Y Llyfr yng Nghymru: Welsh Book Studies No 5 (2003). Available on-line on the National Library web site www.llgc.org.uk .

The Welsh word ‘helynt' means ‘trouble'. Tr.

A very popular short, stylised Welsh poetic form. Tr .

Y Gerddorfa , vol. 3 (1875), p. 44. ‘The English words are by the late Cuhelyn and the Welsh version of them by Mynyddog.'

Emrys Cleaver, Gwyr y Gân (Llandybie, 1964), p. 16.

National Library of Wales MS 21817D, 8 June 1875.

‘Mynyddog's Fourth Book' but the Welsh is incorrect – it should read Pedwerydd Llyfr . Tr.

Personal communication from the publisher's family.

Parry was a freemason for at least the first half of his adult life. Tr.

William Thomas (‘Islwyn') (1832-1878) was a Calvinistic Methodist minister, preacher and poet. Tr.

Parry's birthday. He chose the same day three years later for the first public performance of his opera Blodwen . Tr.

Edward Edwards, ‘Hanes cynnar canu yng Ngholeg Aberystwyth'. Y Cerddor , second series, vol.2 (1932), pp. 299-301.

Joseph Parry's "Aberystwyth"

Frank Bott

When Joseph Parry arrived in Aberystwyth in 1874 to take up the post of Professor of Music at the recently established University College of Wales, he already had a number of successful hymn tunes to his name. Indeed, what is probably the first of Parry's compositions still extant is the hymn tune ‘Fairhaven', which won him joint first prize at the eisteddfod in Fairhaven, Vermont, in 1860 - his second eisteddfod success following winning first prize for his Temperance Vocal March at an eisteddfod held in his family's adopted town of Danville, Pennsylvania.

Parry's six years as Professor of Music in Aberystwyth was not without its troubles – his relationship with the College authorities was often stormy – but it was musically productive and led to the composition of his three best-known pieces: the part song Myfanwy , the grand opera Blodwen , and the hymn tune ‘Aberystwyth'. And it is the last of these that has made the name of its composer and of the small Welsh coastal town where he was living when he wrote it, known not only in Welsh-speaking communities everywhere but also throughout the English-speaking world.

There is some uncertainty about when exactly the hymn tune was written. It first appeared in print in 1879, in the collection Ail Lyfr Tonau ac Emynau [Second Book of Tunes and Hymns], edited by Edward Stephen (1822-85), better known by his bardic name, ‘Tanymarian'. The collection was published by Hughes and Son of Wrexham in two versions, one in sol-fa and one in staff notation. It included three other tunes by Parry: ‘Danville', ‘St Joseph' and ‘ ‘Gogerddan'. The words that were set to ‘Aberystwyth' were ‘Beth sydd imi yn y byd?' [‘What is there for me in the world?'] by Morgan Rhys (1716-79), a hymn with which the tune continues to be associated in Wales to this day. The practicalities of typesetting something as complicated as a hymn book at that time almost certainly mean that the tune was composed at least a year earlier, if not more.

In his sketchy autobiography, never a dependable source of evidence because it was written late in his life, when his memory was unreliable, Parry says that ‘Aberystwyth' was written ‘about 1876'. However, when he published the tune in a book of his hymn tunes in 1888, he gives the date of composition as 3 July 1877.

The former English Congregational Church in Portland Street, Aberystwyth, now a doctor's practice, carries a plaque, with the words:

Cymdeithas Ddinesig Aberystwyth

Eglwys Gynulleidfaol Saesneg oedd yr adeilad hwn

a godwyd yn 1866.

Yma canwyd yr emyn-dôn 'Aberystwyth'

o waith Joseph Parry yn gyhoeddus ar yr organ

am y tro cyntaf yn 1879.

Aberystwyth Civic Society

The hymn tune 'Aberystwyth' composed by Joseph Parry

was first played in public in 1879 on the organ in

this former English Congregational Church built in 1866.

The Civic Society is unable to say what evidence there is for the date of 1879 on the plaque.

Parry was a life-long and devout church-goer, initially a member of the Welsh-speaking Annibynwyr [Independents] and then, after his marriage, a member of the English Congregationalist Church. (His wife, Jane, although from a Welsh family, was born in America and spoke very little Welsh.) A press report in the Aberystwyth Observer tells us that on Sunday 27 August 1876, Parry opened the new organ, built by John Stringer of Hanley, in the English Congregational Church that now carries the plaque. It is tempting to suppose that the date on the plaque is wrong and that ‘Aberystwyth' was written for and first performed on this occasion. While this is plausible, we have, alas, no evidence.

What of the tune itself?

It is in the common 7.7.7.7D meter and in the minor. In Welsh language hymn books it has usually appeared in F# minor or F minor and the latter is still its key in Caneuon Ffydd [‘Songs of Faith'](2001). In The English Hymnal (1906), however, it appears in E minor and this has continued to be the key in most English language hymnals, perhaps because it is easier for unison singing. The tune reaches its climax on the tonic and many congregational singers will find F# or even F difficult to reach. In Wales, with its continuing tradition of four-part congregational singing, this problem does not arise.

While there is nothing startlingly original about the melody, it is well constructed, with eight phrases, of which only the first [A] reoccurs: ABACDEFA. This phrase structure is somewhat unusual but works well and a nice unity is created by the passing notes on the second beat of the bar, which occur once in every line. The modulations – not always Parry's strong point – are well judged and effective: phrase B ends in the dominant major, phrase D begins in the relative major then modulates to the dominant minor at the end of phrase E. Phrase F – the melodic climax – begins (like D) in the relative major before returning to the tonic.

As with the majority of Parry's hymn tunes, the part-writing is highly effective, a far cry from the pedestrian writing so typical of 19th century English hymn tunes, including ‘Hollingside' (see below). ‘Aberystwyth' was obviously written with Welsh congregations in mind; in particular, the tenor and bass lines give ample opportunity for these gentlemen to show off the quality of their voices.

(Parry had a remarkably good musical memory of which he was often unaware. An amusing example of him unwittingly imitating himself is the tune ‘Mynwy', which he wrote some ten years later than ‘Aberystwyth'. Although it is in the major, it bears a close resemblance to ‘Aberystwyth', and a Welsh translation of “Jesu, lover of my soul” is set to it. There are many other examples of Parry unwittingly ‘requoting' himself musically.)

How did ‘Aberystwyth' come to attain its worldwide status as one of greatest of Welsh hymn tunes?

It was a long time before English-speaking congregations had the opportunity to appreciate Welsh hymn tunes. The first edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern , published in 1861, contains no tune that can in any sense be described as Welsh. Oddly, the collection contains a hymn tune called ‘Aberystwith' [sic], written by Rev. Sir Frederick Ouseley specifically for Hymns Ancient and Modern . It bears no relationship whatsoever to Parry's tune; while competently written, it is unremarkable and seems to have been rapidly forgotten. Charles Wesley's hymn “Jesu, lover of my soul”, with which ‘Aberystwyth' is nowadays so firmly associated, is included in the hymnal but is set to J B Dykes' tune ‘Hollingside', which was written specifically for this collection. For many years, the two tunes were to compete for recognition as the standard tune for the hymn and it was not until the 1950s that ‘Aberystwyth' finally attained that status.

‘Aberystwyth' appears in the Baptist Church Hymnal of 1900 - probably its first appearance in an English book - and it is set to ‘Jesu, lover of my soul'. It also appears in the Methodist Hymn Book of 1904, produced jointly by the Wesleyan Methodists and the Methodist New Connexion; there it was set to Charles Wesley's words ‘Sinners, turn, why will ye die?' Despite Parry's adherence to the Congregational Church, the Congregational Church Hymnal published in 1905 by the Congregational Union of England and Wales and which contains close on 700 tunes, contains no tune that is recognisably Welsh. However, when the English Hymnal was published a year later, under the musical editorship of Vaughan Williams, it included some 20 Welsh tunes, including ‘Aberystwyth'. Vaughan Williams (a lifelong agnostic!) had a particular fondness for Welsh hymn tunes; in 1920, he wrote three preludes for organ based on the three Welsh hymn tunes ‘Bryn Calfaria', ‘Rhosymedre' and ‘Hyfrydol'. The English Hymnal rapidly became known as the best of the English hymn books, both because of the fine literary taste shown in the selection of the hymns and because of the breadth and taste shown by Vaughan Williams in selecting and arranging the tunes. It seems likely that it was the influence of the English Hymnal that led English-speaking congregations to appreciate Welsh tunes, ‘Aberystwyth' in particular. This hymn tune was included in the 1916 edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern , later renamed as the standard edition. When Songs of Praise , a hymn book intended primarily for schools, with a strong Anglican, public school leaning, was published, in 1925, the influence of Vaughan Williams was again apparent and ‘Aberystwyth' was included along with a good selection of other fine Welsh tunes, including Parry's ‘Dinbych' and ‘Dies Irae' (known, somewhat perversely, as ‘Merthyr Tydfil' in English to avoid confusion with another tune called ‘Dies Irae'). The enlarged 1931 edition of Songs of Praise also included Parry's ‘St Joseph'. Following the union of the Wesleyan Methodists, the Primitive Methodists and the United Methodists in 1932, a new Methodist hymn book was published in 1933 and included Parry's ‘Aberystwyth', ‘Dinbych' and ‘Dies Irae' as well as a number of other Welsh tunes.

There are many fine Welsh hymn tunes and while ‘Aberystwyth' is good, it is not immediately obvious why it, along with ‘Blaenwern', ‘Hyfrydol' and ‘Cwm Rhondda', should have become so much more popular with English-speaking congregations than tunes such as ‘Bryn Calfaria' or ‘Llangloffan', which have found their way into many English language hymn books but never attained the same popularity. Perhaps the reason is that these three tunes have become associated with particularly fine and popular English words – ‘Aberystwyth' with ‘Jesu, lover of my soul', ‘Blaenwern' with ‘Love divine, all loves excelling' (both hymns by Charles Wesley) and ‘Cwm Rhondda' with ‘Guide me, O thou great Jehovah' by William Williams, also known as ‘Panycelyn' - the only translation of a Welsh hymn into English to become well known.

There are many misstatements and myths about Parry, and the worldwide web has done much to perpetuate them; one of them concerns ‘Aberystwyth'. Numerous web pages, including The Wikipedia page http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nkosi_Sikelel'_iAfrika (as retrieved on 28 December 2014), state that the tune of “Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrica”, the anthem of the African National Congress, which forms part of the national anthem of South Africa and has been used by several other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, is based on ‘Aberystwyth'. Some BBC sites make much of the claim. However, if one listens to recordings of the anthem or looks at the printed music, very little resemblance is discernable. Moreover, the meter of “ Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika” is 9.10.9.6.7.8.6.7, making it more or less impossible to sing the words to a 7.7.7.7D tune such as ‘Aberystwyth'. The most that can be said is that is that if the first phrase of ‘Aberystwyth' is transposed into the major there is a faint resemblance to part of the first phrase of ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika'.

The words of “Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrica” were written by Enoch Sontonga, a young schoolteacher and choral conductor in 1897, when he was teaching in a Methodist mission school near Johannesburg. It is likely that the tune had reached South Africa by then and that Sontonga was familiar with it; certainly it appeared in a Welsh hymn book published by the Welsh church in Cape Town in 1905, the year Sontonga died. Sontonga may even have mentioned the tune in some other context. We have not, however, been able to find any references to ‘Aberystwyth' as the basis of “Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrica” that predate the worldwide web. The source of the myth remains a mystery.

It is clear that Vaughan Williams thought highly of ‘Aberystwyth'. When the Welsh composer Arwel Hughes (1909-1988) was a pupil of his at the Royal College of Music in London, Vaughan Williams told him that he would have been proud to have composed it. Another distinguished and discriminating critic, Dr Percy Young, wrote in his book A History of British Music (Ernest Benn Ltd, London, 1967), “As, however, the last named [‘Aberystwyth'] is the noblest work of its kind composed by a British musician, Parry achieved more than many whose reputations were and sometimes are, said to stand higher.”

I am most grateful to Dr Rhidian Griffiths who read an earlier version of this article and made many valuable suggestions, as well as drawing my attention to several important facts and pointing out a number of errors.

Joseph Parry's ‘Cytgan y Morwyr'

Dulais Rhys/Frank Bott

Cytgan (1) y Morwyr [The Sailors' Chorus] was written around 1874 for unaccompanied male voices in four parts (TTBB – two tenor and two bass parts) on words by Mynyddog (Richard Davies of Llanbrynmair), a well-known Welsh poet and friend of Parry. This short piece complements longer TTBB works by Parry such as Iesu o Nazareth [Jesus of Nazareth], Cytgan y Pererinion [The Pilgrims' Chorus] and most famously, Myfanwy.

Cytgan y Morwyr was written shortly after Parry's appointment as Professor of Music in October, 1874 at the recently founded University College of Wales in Aberystwyth. His department grew quickly and developed an excellent mixed choir. Presumably on Parry's insistence, female students were admitted to the Music Department, although the College was otherwise all male. Parry wrote much of his music of this era with this choir in mind and though there seems to be no specific reason why Parry wrote Cytgan y Morwyr – not that he need much persuading to start any composition – it would be logical to assume that it was written for the Tenors and Basses in his student choir.

Cytgan y Morwyr was first performed in a Music Department concert at Aberystwyth's Temperance Hall (the venue of the première of Parry's Blodwen – the first Welsh opera, 1878) on 18 December 1874. Featuring the department's singers, Cytgan y Morwyr was the opening item – a sign possibly that Parry wanted to start the concert with a bang.

Mynyddog's Welsh text is competent if conventional, presenting the usual romanticised view of a sailor's life. When the work was published, it included an English translation by Cynonfardd (Rev. T C Edwards), which is both inaccurate and poetically inferior to the original. The text consists of three stanzas of 8.6.8.6.7.7.7.7.9. Parry sets the first two strophically (same music with different words) in the minor and the third stanza to different but related music in the tonic major - a fitting climax to one of the composer's shorter choral gems

Harmonically, Cytgan y Morwyr is mostly chordal (homophonic) and in the minor, with the music fluctuating between a raised and lowered 7 th degree of the minor scale – the latter creating a modal and ‘sea-shanty' effect.

Cytgan y Morwyr was published in Cardiff in 1893 by Hughes a'i Fab ( Hughes and Son ), the Wrexham printers who had printed much of Parry's earlier work but had by then started to publish in Cardiff. It was published as ‘Opus 20' - a seemingly arbitrary catalogue number in Parry's list of published works by different companies - citing the work to be “in great demand”, presumably by Wales' many male voice choirs of the era. Less conventionally, the chorus was performed on 4 August 1893 on boats on Y Bala's lake Llyn Tegid – presumably in an effort to connect with the nautical nature of the work.

Cytgan y Morwyr – along with other Parry favourites listed above – was a staple in the repertoire of Welsh male voice choirs until the mid-20th century. Since then, especially with the decline in choir membership in general and in an effort to attract young(er) male singers, Parry's TTBB works have gradually been replaced with easier-to-sing and arguably ‘more popular' lighter pieces such as male voice arrangements of pop songs and choruses from easy-on-the-ear musicals such as Les Miserables.

When the work was first published the first word of the title was spelt ‘Cydgan' [Chorus]. Welsh spelling was revised in 1928 and ‘Cytgan' is the modern spelling.

Parry’s 1894 American Tour

Frank Bott

At the beginning of April 1894, Jane and Joseph Parry were bowled over by the devastating news of the unexpected death of their eldest son Joseph Haydn, at the age of 29, leaving a widow and two small children. This came on top of the death, two years earlier, of their youngest son, William Sterndale. Parry decided that a trip to America would be good for himself and his wife. They had last made the trip as a family in 1880, although Jane and their youngest daughter had made a trip in 1887.

A purely private trip was not really feasible. The cost would be high and, anyway, the Welsh community in America would, reasonably enough given their support for his education at the Royal Academy, expect opportunities to see and hear him. Accordingly, Parry asked the Rev. Thomas Edwards (‘Cynonfardd’)(1), of Edwardsville, Pennsylvania, to publicise the forthcoming visit in the Welsh press and invite the Welsh communities to contact him if they wished Parry to speak in their area. He emphasised Joseph’s connections with America and how a warm welcome would help the family forget their recent tragedies. Welsh America responded well to the appeal, and Cynonfardd arranged a timetable for the tour that, although quite demanding, did give Parry some free time to spend with his family and old friends. He led cymanfaoedd canu, adjudicated in eisteddfodau, and delivered lectures to Welsh communities across north-eastern America. On many occasions he sang ‘Make New Friends but Keep the Old’(2), a solo he composed in 1886, whose text sums up his feelings towards the people of the country where he passed his formative years.

The trip proved to be enjoyable and successful. It was reported on at some length in four articles in the Western Mail, the Cardiff-based South Wales daily newspaper. These articles are reproduced below, with annotations, using the original (and occasionally eccentric) language and orthography.

* * *

From the Western Mail, 6 August 1894

Dr. Joseph Parry in America.

______________

Interesting letters from the Welsh Musician.

______________

Incidents on the trip across the Atlantic.

______________

Enthusiastic Welcome at Scranton.

______________

Dr Joseph Parry, the distinguished Welsh musician, started for America on June 23, and is now engaged in touring the States and in delivering lectures on “Music” in the numerous Welsh centres which exist amid the teaming populations of the great American Republic. We have been favoured with several communications from the doctor, giving an interesting narrative of the incidents of his trip across the Atlantic, and of his doings up to July 13, and these have been supplemented by newspaper cuttings which have reached us describing the enthusiastic receptions which have been accorded to the talented Welshman since his arrival in America. We are unable to give Dr Parry’s letters in full, but publish below portions of them.

Dr. Parry, Mrs. Parry, Miss Dilys Parry, Miss Blanche Clarke, Cardiff, Mr Greville (Dr Parry’s cousin (3)), and Mrs Greville, forming a cosy little party, embarked on the steamship Umbria, a Cunard liner, at 4.30 p.m. on June 23 and at 4.45 o’clock were on the way to Queenstown. A thick fog prevailed, but Queenstown was reached in safety at seven o’clock on Sunday morning, June 24, and a wait was made for the noon mail. By Monday morning the Umbria, with 198 saloon passengers, 112 intermediate passengers, 271 steerage passengers, and 294 officers, seamen, and firemen on board, was far away from the busy haunts of man – a floating village in an oceanic world! For the first few days the weather was foggy and somewhat rough, but the doctor jubilantly informs us that he managed this time to escape sea-sickness. In describing the steamer Dr. Parry says:–

The magnificent dining-saloon, with five long tables, also each state or bedroom, as well as all the passages, are lit with electric light, so that nights on board are as days. There is a fine American organ with 25 stops. It is a most orchestral-like instrument. A finer one I never played on. Its beauty of tone and variety of effects really inspires one.

The fog continued until the Friday morning, when the sun broke through the atmospherical veil, and everything became bright and cheerful. A strange coincidence is mentioned by Dr. Parry. On board the steamer was a Mrs Martin, from Ohio, whom Dr. and Mrs. Parry had met on the Berlin, from Liverpool to New York, in 1880. Neither of them had crossed from England to New York in the meantime. The Umbria arrived in New York on Saturday evening, June 30, and the passengers landed on Sunday morning. Several of Dr. and Mrs. Parry’s relatives had journeyed to New York to meet them, and they were accompanied by Mr. J. M. Price (Dr. Parry’s first teacher in harmony and composition) and the successful vocalist Professor J. W. Parson Price (4) . Writing under date July 13, the doctor says:–

On Monday we left New York by the nine a.m. train for Scranton. On our arrival there an old friend, Judge H. M. Edwards(5) , Mrs Edwards, and many others met us, and we spent one of the happiest of weeks at the judge’s house. And it was a most eventful week, the programme being an eisteddfod on July 4, a grand reception on the 5th, and my lecture on the 6th. The reception was one that I shall never forget as long as my memory lasts. The many speeches of my old friends took us all back full 30 years to the happy days gone by. I seemed to see again many faces and bright smiles that vanished for ever, and sweet voices that made music in our ears years ago seemed to be with us once more. Yes, this meeting was truly a sweetly sad one, and I shall never forget it. This fine city of Scranton has made wonderful strides. Electric cars are seen creeping through all the city streets, as well as to all the suburbs. All the streets and the houses are lit by electricity. A drive through the shady avenues by night disclosed a scene like fairyland, so very beautiful are the streets, houses, and the lights. On Sunday night at eight we attended Elm Park-street Methodist Church, the most idealistic church I ever saw. It is more like a palace concert-room. The sittings for 2,000 were well filled, and the church was brilliantly lit with huge and magnificent chandeliers – electrically, of course – and the accompaniments were played on a magnificent organ, worth about £3,000, and worked by electricity(6) . They had here the usual quartette of engaged artistes, who each received 40dols. to 60dols., the young organist having 160dols. per annum. We called at Kingston, twenty miles from Scranton, and there saw my sister(7) and family, also our dear old friends the Hon. Daniel Edwards and family, and the Rev. T. C. Edwards, D.D. (late of South Wales), and his happy family. We are now in Danville, still 50 miles lower down, where my wife’s brother and sister live, and where we lived for fully twenty years. Words would fail to convey our feelings on our visit to this dear old place. We found there a new generation, the old friends having nearly all passed away. Tomorrow I commence my lecture tour at Kingston. On Monday, the 16th, I will be at Shamokin, at Plymouth on the 17th, and Wilkes-Barre on the 18th. From there I shall go some 308 miles to Johnston on the 20th. I shall be at Pittsburgh on the 21st, Youngstown (Ohio) on the 25th, Cleveland City on the 28th, Gomer on the 30th, and Cincinnati city on August 2. Then I have a long journey to Chicago and Illinois, and from there I proceed to the State of Wisconsin. I shall have to be back, however, to this State and district of Scranton and Wilkes-Barre for a two-day large eisteddfod, and I am booked to give a series of lectures and an orchestral concert. Some hymn tune festivals at Philadelphia and New York cities will conclude my tour. In accordance with a promise made to Mr. Lascelles Carr(8) , I hope to keep the “Western Mail,” and through that widely-circulated journal all my friends informed of my movements.

The American papers published in Scranton and the other towns visited by Dr. Parry have been giving exhaustive reports of his lectures and speak of him as ”the most famous of the musicians of Wales,” “the pioneer of Welsh opera,” &c. The ”Scranton Tribune” of July 3 thus refers to the doctor’s appearance:–

Dr. Parry is a middle-aged, dignified, and pleasant gentleman. His long silver hair gives him the appearance of a born composer. He was much impressed with the remarkable growth and progress made in every direction in this city, which place he has not visited since twenty years. Dr. Parry was born in Wales and came to this country many years ago, locating at Danville. Residing there for a time he afterwards returned to Wales, where he has become one of the most famous and recognised of Cymry’s bevy of musical masters. He is well acquainted with numerous musicians and residents in this city and valley. His works have made him famous throughout the civilised worlds, and his name in musical matters has always been upheld as authority.

Describing the reception tendered to Dr. Parry in the First Welsh Congregational Church on South Main-avenue, the “Scranton Tribune” says that Judge Edwards took the chair, and the meeting was a most enthusiastic one. The Rev. David Jones, pastor of the church, delivered a short address in Welsh, and was followed in English by Attorney W. Gaylord Thomas, who said that Dr. Parry was worthy of all the honours they could bestow on him. There was no Welshman who adopted that county as his home but what became a good patriotic American. There were no Anarchistic or Socialistic ideas in him, and this he attributed to the refining and elevating qualities of music, in which the Welshman was so proficient. The Hon. Morgan P. Williams(9) , of Wilkes-Barre, then spoke in Welsh, and was followed by Mr. A. J. Colborn, jun.,(10) a native of Somersetshire. Mr Benjamin Hughes, the last speaker, added an eloquent tribute to the praises showered on the doctor. Having replied, Dr. Parry sang a song of his own composition, entitled, “Make new friends, but keep the old,” with great success. At Mear’s-hall Dr. Parry delivered a really able lecture on “Music,” in which he intimated that his ambition in life was to establish a Welsh national academy of music, and in which he put forward powerful pleas for the cultivation and development of musical art.

* * *

From the Western Mail, 5 September 1894

Dr. Joseph Parry in America.

______________

Progress of his holiday tour.

______________

Further Correspondence from the talented Welshman.

______________

Interesting References to Welsh People and Welsh Places.

______________

The Great Chatauqua Chorus.

______________

From the tenour of a further series of letters received from Dr. Joseph Parry, of the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire, who is now spending a holiday in America, it would appear that the eminent Welsh musician has received cordial welcomes wherever he has gone. His last letters were from Danville (Pa.) and Scranton, and in his third letter he describes a visit to Johnstown, where the great disaster of 1889 took place(11) . “Nearly the whole of the town,” says Dr. Parry, “has been re-built. Along the river for five miles run an extensive steel works, called the Cambrian, at which from 5,000 to 6,000 hands are employed. Electricity is largely used by the population, which is about 35,000. At Pittsburgh (Pa.) there are 45 rolling mills, and electricity and electric forces reign supreme in this city, which is remarkable for its commercial enterprise. Here my friend and fellow countryman, Mr. T. C. Jenkins, has enormous stores, covering a whole square, six storeys high. The goods are taken by means of a railway into the very centre of the building, and nearly 200 hands are employed.”

Dr. Parry goes on to describe the beauties of Youngstown, Ohio (where he met many old friends), and the wonders of Cleveland, which he visited on July 28. In Cleveland there are nine rolling mills, one of them employing 4,000 men. He found here many of the friends of his youth, and his lecture was quite a success, it being followed by a fine selection of vocal music, discoursed by an able male party, comprising some of his old pupils.

Dr. Parry’s last letter we quote almost in extensor. It is as follows:–

In my last letter I wrote of beautiful Cleveland, Ohio. My next visit was to the charming town of Lima, where I stayed with my dear old Aberystwith pupil, Mrs. Daniel Alltwen Bell(12) . Two other pupils, formerly of the same college, came here to meet me, and there was a delightful re-union. Mrs. Nellie Owen Hibler(13) was one, and she came fully 350 miles. Mr David Davies, Cincinnati(14) , was the other, who lived some 150 miles away. I gave my lecture, assisted by fine selections by my three pupils at Ganer. This is a magnificent agricultural district, of fine and wealthy Welsh people, all from Montgomeryshire. They have a fine church, and one of the most popular of places for a concert or lecture. On previous occasions when I visited this place I was always welcomed by a full church, and so this time. The ever-popular Drs. Jones and Davies, who have practised together for full 30 years are always kind and genial. It is now 28 years since my first visit to this place, some ten miles from the railway depot of Lima. The next day, after some six hours’ train ride, the great city of Cincinnati was reached, and I once more stood by the house where “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was written. I also found that I stayed the night within a mile and a half of the locality where the plot of my son Haydn’s last opera, “Miami.” was laid. The next evening I left by the 8.45 train for, and landed the next morning at eight in, the great city of Chicago. I spent here the greater part of a week. Tongue and pen must ever fail to describe this the greatest city, in many respects, of modern times. I found here no less than nine churches for the coloured people, with choirs, organists, and orchestras of their own. After a whole night’s travelling (in a sleeper) I came to the most idealistic of places, Chatauqua(15) , N.Y. Lake Chatauqua is 26 miles long, and contains some charming islands. The village itself is hidden in the foliage. Now, in the months of June, July, and August there are no less than 12,000 to 15,000 visitors here, consisting of students and the most learned and distinguished professors, reverends, and principals, not only of America, but from all parts of the world. It is a university in Paradise. There are fine colleges, and in almost all departments the amphitheatre is a sight worth seeing. Some 8,000 learned people listening to lectures, sermons, and the singing of the whole of the congregation in praising God has an effect not to be forgotten. Their musical college was to me an attractive feature. The principal (Dr. H. R. Palmer(16) ) and I were fellow students 33 years ago, and we had not met from that time till now. Our feelings can, therefore, be better guessed at than described. Then young, and with the world before us; now grey with our labours. He was exceedingly kind. His choir of over 500 consists of members from the various States. Through the courtesy of the doctor I was supplied with a list, which shows the popularity of the place and the distances from the various states:–

Chatauqua Chorus enrolment from July1 to August 11, 1894:– From Pennsylvania, 100 miles (166); New York, 450 miles; Ohio, 400 miles (83); Minnesota, 1,000 miles (1); Iowa, 900 miles (7); Tennessee, 800 miles (7); Kentucky, 600 miles (4); Maine, 800 miles (1); Texas, 1,800 miles (5); Georgia, 899 miles (3); Virginia, 600 miles (2); West Virginia, 600 miles (4); South Carolina, 900 miles (2); Mississippi, 800 miles (2); Massachusetts, 700 miles (5); Colorado, 1,000 miles (1); California, 3,000 miles (1); Florida, 1,200 miles (2); Michigan, 300 miles (3); Kansas, 1,000 miles (2); Wisconsin, 600 miles (3); Vermont, 600 miles (1); New Jersey, 400 miles (17); Indiana, 450 miles (11); Maryland, 600 miles (2); Illinois, 500 miles (24); Missouri, 700 miles (7); Connecticut, 450 miles (7); Arkansas, 800 miles (4); Louisiana, 1,200 miles (4); Canada, 100 miles (7); British West Indies, 2,000 miles (1); England (3). These distances are approximate, as the States are from 100 to 500 miles from boundary to boundary.–Miss Ella F. Case, secretary.

Professor Sherwood(17) is one of America’s greatest pianists. A pupil of Rubinstein and Liszt, he is a remarkable performer, and as modest as he is great. He teaches the pianoforte here. There are some dozen piano practising cottages, all detached, and some fine recitals are given. I heard two. Professor Listusuan, violinist, is another true artist and performer. He teaches his instruments here in the summer. There are professors at this place in all branches of learning, and so successful has this school of only twenty years’ existence been that there are no less than 60 Chatauqua branches all over the States. The educational work, therefore, supplied by them is incalculable.. Dr. Palmer’s work is great. He has the genius to popularise our great art. I would call him the Dr. Hullah(18) and Curwen(19) of America. I shall never forget my visit to Chatauqua, with its atmosphere of learning and true virtue. All are busy here from the early hours of the morning. Long may the grand work of this beautiful place flourish.

* * *

From the Western Mail, 6 October 1894

Dr. Joseph Parry in America.

______________

Visit to Mahoning.

______________

The “Montour American” of September 20 devotes nearly a column to a description of Dr. Joseph Parry’s visit to Mahoning(20) and his lecture on music at the Presbyterian Church in that place on the previous Thursday evening. “This testimonial lecture and concert,” says our Yankee contemporary, “were given in compliance with a request that had been made by a petition signed by many of our leading citizens asking Dr. Parry that, before his departing for home, he should give the people of our town an opportunity to publicly express their appreciation of his ability and the success he had attained in the musical world, and to compliment him upon the honours that had been awarded to him during the past few years. The evening was pleasant and the church was well filled with an intelligent and appreciative audience.

“Dr. Parry rendered a selection entitled ‘Make New Friends but Keep the Old,’ the music and words of which were composed and written by himself. The doctor’s voice is a baritone of great volume, splendidly cultivated and under perfect control. The words were appropriate and most suitable, and were sung in a sympathetic and expressive manner. During the singing of the piece the doctor accompanied himself upon the piano, as he also played the accompaniment for the others who sang. The lecture was divided into two parts, the first of which was entitled, ‘History, Forms, Styles and Masters of Music,’ and was delivered immediately following the singing of his solo above mentioned.

“He followed the subject closely and intelligently. Going back before the birth of Christ, he spoke of the origin of music and the advancement it had made as it came down through the ages, and of the perfection it had reached in the closing days of the nineteenth century. He soon convinced his audience that as a careful musical student he had a thorough acquaintance with the history, forms, and styles of music, and in beautiful language depicted its progress and the elevating and refining influence it has had upon the civilisations of the world, and when he touched upon the masters of music he forcibly impressed his hearers with the fact that his knowledge of men was as great as was his information of their works, and in rapid succession gave the names, dates, and productions of the great masters of the past, as well as those of modern times.

“The second part of his lecture was entitled ‘The Music and the Musicians of Wales.’ Here, too, he demonstrated that he was upon familiar ground, and was thoroughly in touch and sympathy with the men and music of his native country. He carried us back to the time of the Druids, who figured so conspicuously in Welsh history during the first century, spoke of the massacre of a thousand of them at one time by the Romans at Anglesey, but that it did not decrease their ardour or love for the Welsh airs, and so great was this love and devotion to this art, crude as it was, that even Edward, King of all England, found it was absolutely necessary to exterminate all the bards before he could subjugate Wales. Though he drove away the workmen, the work went on, for such an impression had been made upon the minds and hearts of those who had heard this music and had so permeated the great heart of Wales that their manners and customs were influenced by it, and in new songs and national airs there broke forth continually the pent up melody which in more recent years has placed Wales and the Welsh race in the forefront of the composers and singers of the world(21) . Poor in worldly things they were yet rich in culture and song; wherever they have gone or wherever they are, at home or abroad, they carry with them the love of music in all its forms, and the unbiased thinker must admit that no people or country has contributed more to promote singing by the masses than the Welsh, and this is particularly true of congregational singing.”

* * *

From the Western Mail, 22 October 1894

Dr. Joseph Parry’s tour.

______________

Some Welshmen he met in America.

______________

Welsh-Americans and Next Year’s Eisteddfod.

______________

Judge Edwards coming over.

______________

MR JAMES SAUVAGE AS A NEW YORKER.

______________

A “Western Mail” representative a day or two ago had an interesting chat with Dr. Joseph Parry, of the University College, Cardiff, who, fresh from his visit to America, was full of reminiscences of American places and Welshmen in America.

“I don’t think I mentioned in my last letter to the ‘Western Mail,’” said the genial doctor, turning his mind back over the incidents of his tour, “that I visited the City of Brotherly Love – Philadelphia. It is a city unique in the matter of beautiful roads, fine buildings, electric street cars, and has a magnificent opera-house. In the latter building they hold a summer season of operas by Hinricks(22) , and there I heard Gounod’s ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ ‘Carmen’, ‘Rusticana,’ and ‘Il Trovatore.’ The principals were really good, and the orchestra very fine, but the chorus was weak – especially the male voice. I also visited the rolling mill, where I found many of my old friends of my boyhood days – among them being Mr. Lloyd, the manager of the mill, my brother-in-law, Mr. Lewis(23) ; Mr. James, of Merthyr (formerly drummer in the Cyfarthfa Band); Mr. Young, and Mr. Hughes (son of the late Mr. Hughes, the owner of the works), who is now solely responsible for the mill. I also met two other Welshmen in this city whose names I should not omit to mention, viz., my young professional friend, Mr Henry Jones, and Colonel Davies, of the Custom-house there. I went to the spot where William Penn landed, and where the treaty was signed between William Penn and the Indian natives in 1682, and where a monument has been erected. On most of my Sundays I held, by invitation, congregational singing meetings in the church of Dr. Edwards, late of Cardiff, who arranged my tour. Dr. Edwards’s church is a beautiful building, and an organ, worth £300, has just been erected in it. Mr. Daniel Edwards, a thorough Welshman and a man of immense wealth, is a member of the Church. While speaking of the Welsh Welshmen I met, I ought not to forget the Hon. Judge H. M. Edwards, of Scranton, Penn., who is one of the ablest and most distinguished Welshmen in America. I have very great pleasure in stating that we in Wales may be favoured with a visit from his Honour during the time of the Llanelly Eisteddfod, and I hope if he does come, that he will be asked to preside over one of the meetings. Judge Edwards is, I believe, a native of Ebbw Vale. He is a fine orator in either Welsh or English, a poet of ability, and an able scholar. In New York City, I spent the whole of Sunday – morning, afternoon, and evening – in promoting congregational singing. I met here a lady whom many will remember, viz., Mrs. Dr. Peek (nee Miss Susannah Evans), who is doing splendid work as a lecturess on temperance. I also came across my fellow professional, Mr. J. W. Parsons Price, of Aberdare, who is one of the finest vocal teachers in New York City, and holds an important position there. There was also another distinguished Welshman there – Mr. William James, who is the manager of the New York City and Hudson Railway(24) . Mr. James is a very excellent tenor singer. There also was Mr. John M. Price of Rhymney. Another interesting renewal of acquaintanceship was that with Mr. James Sauvage (25) , who, together with his son Tongo and Miss Glanmarchlyn Owen, kindly participated in my lecture concert. There is but one opinion in New York City about Mr. Sauvage, and it is that he is one of the finest baritones in the city. I visited his church in Newark (New Jersey), a magnificent building – in fact its architectural beauty was beyond anything I have ever seen. Mr Tongo is organist, and occupies a first-class position there. While there I shook hands with Mr. Charles Jones, brother of Mr. Henry Jones, the Docks, Cardiff, and his son Thomas. During my week’s visit to Brooklyn I spent a considerable time with Mr. Prodgers and his good lady, who are acquaintances of 32 years’ standing. Mr. Prodgers was born and bred in Cardiff, and his father before him. Brooklyn is a fine city, with its bridge of wonderful construction. This bridge took twenty years to build.”

“And how are Welsh musicians, generally speaking, progressing in America?”

“My fellow Welsh musicians will be glad to know that our countrymen in America are making substantial and rapid progress in music. They have their choral societies there and hold some very good eisteddfodau, and after listening to competitions there I was bound to admit they are almost equal in ability to our own. The male voice choirs, which are very numerous, are also really very good, and the societies of mixed voices equal many of our societies in Wales. It would be invidious to name only a few of the conductors, but none will, I am sure, feel offended at my speaking of Mr. Haydn Evans, the winner of the Chicago prize, and my old pupil, Mr. Daniel Protheroe(26) , who is making a name for himself in America. He has just now been called to the fine city of Milwaukee, of the state of Wisconsin. In the way of teachers they have some very good examples who are doing well. Many Welsh musicians will be glad to hear of the success of the very able and distinguished Welsh lady pianist of Chicago, Miss Moses. Her father is an old friend of mine. Miss Moses studied at Leipsig [sic] for three years, and when I heard one of her recitals at the musical college in Chicago, I at once saw that she was a pianist of very high order.”

“You were well received in America, Dr?” said the reporter.

“Yes, very cordially, and I cannot express my appreciation of the great kindness which I received in every place I visited. Having spent twenty years in America – from my boyhood up – it was like a return home, and the Welsh-Americans there regarded me as one of themselves. The hospitality and good feelings displayed towards me were such that I can never forget. A great many of my friends asked me to renew my visit, but I have not made up my mind on that score yet.”

* * *

1. The Rev. Thomas Edwards (1848–1927), ‘Cynonfardd’. Independent minister born in Landore (Swansea). The Dr Edwards Memorial Church in Edwardsville is named after him and has continued to hold an annual Cynonfardd Eisteddfod to this day.

2. The original Welsh title of the song was ‘Y Cyfaill Pur’ (‘The True Friend’) but it became generally known in English as ‘Make New Friends but Keep the Old’.

3. This is the only reference to a cousin of Parry of which we are aware.

4. J.W. Parson Price (1839-1918). Originally from Beulah in Breconshire. Singer, teacher and composer of ballads and hymn tunes. He emigrated to America in 1864 and, after a successful career as an operatic tenor, settled in New York as a music teacher.

5. Henry M. Edwards (1844?-1925). Originally from Blackwood in Monmouthshire. Settled in Scranton in 1864. He flourished as a journalist and writer, and developed an expertise in legal matters. In 1892 he was nominated as Lackawanna County Judge, in which position he served unopposed until 1923. He was a leading figure in local politics and the undisputed leader of the Welsh community in Scranton.